The Tournament, as held in the 14th and 15th centuries, was an event of great pomp, ceremony and pageantry. Basically a "contest@ between the @forces@ of two opposing men of high nobility,

it afforded the combatants with an opportunity to show off their martial

equestrian skills, and provided the populace with a grand demonstration of the

valor of knights and fighting men. The Emprise as it is practiced in the SCA

today is derived from the customs of the Tournament of these times. It is

therefore worthwhile for the SCA equestrian to study the treatise of King René

in order to gain a better understanding of the tradition of the tournament and

the reasons for the procedures used in the Emprise.

The Tournament, as held in the 14th and 15th centuries, was an event of great pomp, ceremony and pageantry. Basically a "contest@ between the @forces@ of two opposing men of high nobility,

it afforded the combatants with an opportunity to show off their martial

equestrian skills, and provided the populace with a grand demonstration of the

valor of knights and fighting men. The Emprise as it is practiced in the SCA

today is derived from the customs of the Tournament of these times. It is

therefore worthwhile for the SCA equestrian to study the treatise of King René

in order to gain a better understanding of the tradition of the tournament and

the reasons for the procedures used in the Emprise.

René of Anjou, a politician as

well as a military man, is well known to history as a patron of the arts. His

titles include: Count of Provence, Duke of Anjou, Bar and Lorraine, and King of

Jerusalem and Sicily. He was also an author and wrote several poetry works, as

well as: the Mortiffiement de Vaine Plaisance, a religious allegory

(1455); the Livre du Cuer d'Amours Espris, a romantic allegory (1457);

and the Forme et Devis d'un Tournoy, a treatise on how to hold a

tournament (1460).

In his book, René proposes to

explain the forms, customs and procedures for conducting a Tournament. As he

states, AHereafter

follows the form and manner in which a tourney ought to be undertaken. And

in order to organize and carry out this tourney well and honorably and in the

right way, you must keep to the order hereafter described.@ René

organized several extravagant tournaments including a tourney at Nancy in 1445,

celebrating the marriage of his two daughters Marguerite and Yolande; the

Emprise de la Gueule du Dragon at Razilly; the Emprise de la Joyous Garde, at

Saumur, both in 1446; and the Pas de la Bergère at Tarascon, in 1449. So, it

seems he is appropriately suited to write such a treatise.

He begins by stating that it

would be courteous if the Prince holding the tournament would secretly write to

his Aopponent,@ or other nobleman asking if he would

participate in the tournament. This would save him the embarrassment of having

to decline in public if, for some reason, he was unable to attend or

participate. René explains that the

prince or nobleman hosting the tournament is referred to as Athe appellant,@

His Aopponent@ is called the Adefendant.@

He details that Athe king of arms@

should be sent by the appellant, bearing a Tourney sword, as a symbol of the

Tournament, and that he should present it to the defendant, asking him to

participate in the Tournament. This is to be done with the greatest amount of

ceremony in a very public place (once the secret message was confirmed). The

appellant prince should select 8 potential judges -knights and squires, half

from his lands, and half from his Aopponent=s@

lands who are men of great martial skill themselves. René sets out the exact

wording that can be used in these matters, all of which is full of pageantry,

and truly conveys the flamboyant nature of these proceedings. He explains in what way the defendant could

state that he was forced to decline, if that was the case, and maintain his

honor in doing so. He also states how the defendant would go about accepting

the offer of a Tournament, and how he would then review a scroll presented to

him by Athe king

of arms.@ This

scroll would include the Ablazons@ of the prospective judges, which the

defendant could study and pick from to determine the final list of judges for

the Tournament. We here see that the >King

of Arms@ is meant

to be what we know in the SCA as a Herald. The scroll contains the heraldic

arms of the men proposed to judge the Tournament. The defendant, it is

understood, would know these men by their heraldic devices and be able to

determine if he wanted them to participate. And so, we can see that those men

put forth by the appellant truly must have been men of renown that they would

be well known by their heraldry alone.

René details how the king of

arms, the Herald, should notify the judges that they have been asked to

participate in the Tournament. He lists the benefits of a Tournament as

follows:

First, Aall

may know which men are come of ancient nobility, by the way they bear arms and

crests.

Second, those who have failed to behave honorably will be

chastised so that the next time they will be wary of doing that which is not

fitting for honor.

Third, each one who takes up the sword will get good

exercise of arms.

Additionally, if they hold a

good Tournament, Athe

tourney will take place in such a way that fame and widespread rumor will go

out to sustain nobility and increase honor.@

If the Judges accept, which we

can suppose most would have done, they set a date and time for the

Tournament. The Herald is tasked with

going back to the appellant and defendant, and to the King, and telling them this

information. Additional courts would be

sent invitations as well, whether by this main Herald, or his delegates. And they should Acry

the tourney in the places appropriate.@ René details the manner and form in which

they should do this.

|

| From Tunierbuch, showing straw-filled hourts on the horses. |

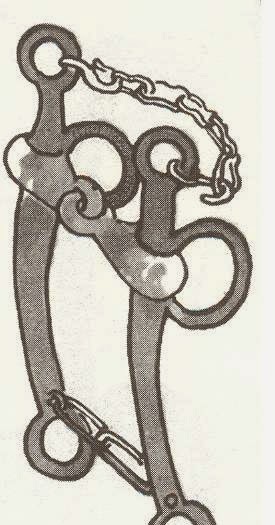

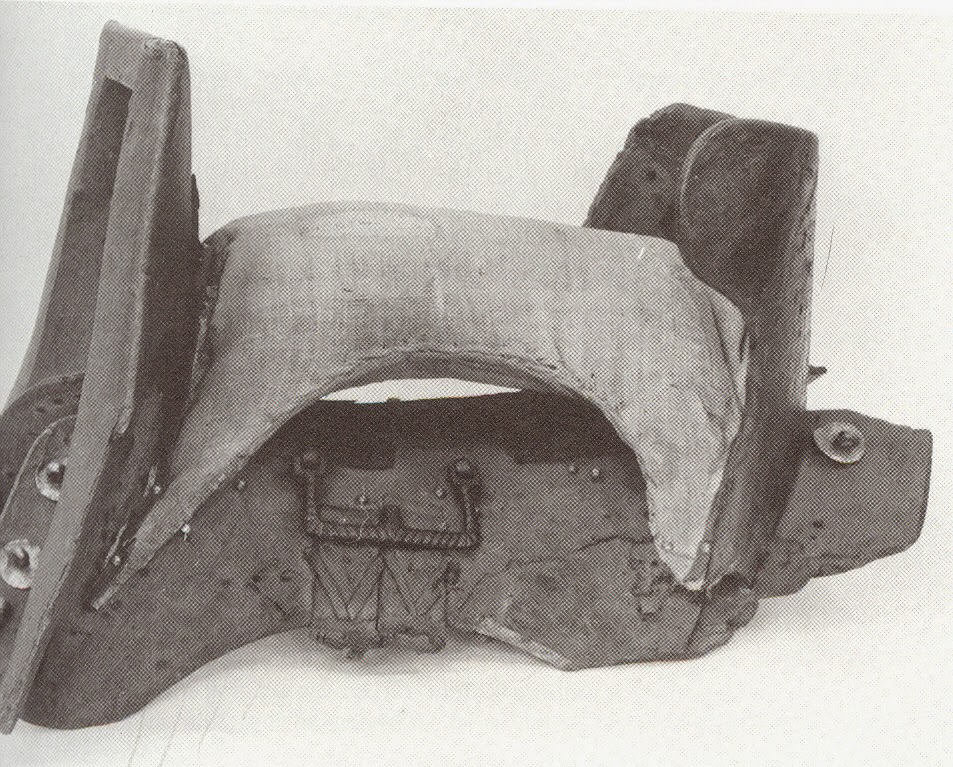

In the next part of his

treatise, René covers the equipment of the mounted warrior, his crest, mantling

and armor, as well as his weapons, tack and protection for the horse. For the latter, he suggests a Ahourt@

made of straw stuffed cloth, sew in a crescent shape that straps to the chest

of the horse and protects it from weapons=

blows and kicks by the opponent=s

horses. (This section of René’s book

provides a wealth of information of benefit to the SCA equestrian researcher.)

René describes the lists:

A

The barriers ought to be one-fourth longer than wide, and of

the height of a man, or of the length of an arm and a half, of strong wood and

with two crossbars, the one high and the other at knee- level. They should be

double; that is to say a second barrier four feet outside the first barrier, to

refresh the foot servants, and protect them from the press; and within this

space should be the armed and unarmed men ordered by the judges to protect the

tourneyers from the crowd. And as to the size of the lists, they should be

bigger or smaller according to the number of tourneyers and the opinion of the

judges.@

René continues to explain the

customs and rules of the Tournament. The appellant brings his Lance to the

Tournament, as does the defendant, and he is referred to by René as >the captain.@

He suggests that those noble warriors desiring to compete in the Tournament

must present themselves on the Thursday before the Tournament, in all manner of

pageantry. René suggests the participants enter the town with a great

procession. The captain=s

main battle horse, or destrier, should proudly bear his heraldic arms, and be

mounted by a small page. The horse should have ostrich feathers mounted on its

head and bells collared around its neck. Behind should come the horses of the

knights and squires of the company, walking two by two, in high fashion, decked

out in their finest barding bearing their master=s

heraldic arms. Behind these should be a great pack of trumpeters, minstrels,

and heralds dressed in the nobleman=s

heraldic arms. Behind them walks the knights and squires who will actually

participate in the Tournament. And behind them, their followers bring up the

rear of the procession.

At the inn where the

participant takes up residence, participants must display their arms. René says

lords and noblemen should do it in this manner: AHe

should have the heralds and pursuivants put up a long board attached to the

wall in front of his lodgings, on which is painted his blazon, that is to say

his crest and shield, and those of his company who will take part in the

tourney, knights and squires alike. And he should have his banner displayed at

a high window of the inn, hanging over the road@

Additionally, captains of companies, should additionally display their pennons

with their banners, and Abarons

who put up their banners at the windows are required on their honor to display

the coats of arms of at least five other tourneyers with their banners, as a

company.@

The judges entry to the city is

no less ceremonious. René details how

they should enter town and go to a cloister, if possible, to set up residence

during the Tournament. At this place, the participants in the Tournament

display their crest and banners to be visited by and shown to the ladies. There

the judges also display their heraldic arms. AAnd

the judges should have in front of their inn a cloth three arms'-lengths high

and two wide, on which are drawn the banners of the four judges held by the

king of arms who cried the festival, and above at the top of the cloth should

be written the two names of the captains of the tourney, that is, the appellant

and the defendant, and at the foot, below the four banners, should be written

the names, surnames, lordships, titles and offices of the four judges.@

On the evening of the arrival

of the participants and the judges, there should be a great feast. The ladies

and damsels who have come to watch the Tournament, and in whose honor it is

held, attend this feast, as does the heralds. The folks there should eat, and

dance and then the Heralds announce that the participants must, on the next

day, present their crest and banners to the house where the judges are staying.

Additionally, this next day is a day of rest for the tourneyers, followed by

another feast with dancing and revelry.

The next day the crest and

banners are displayed and the ladies come to view them. René details how they

are walked around the hall to look at each participants=

gear. Heralds will tell the ladies who each participant is in case they do not

know them by their arms. This display of arms is really, in essence, a judgment

of the valor and merit of the participants and whether or not they will be

permitted to participate in the Tournament. René =s

treatise goes into great detail about how men who were guilty of several offenses

would be treated. It is as though they are seen as besmirching the glory and

honor of the Tournament by attempting to enter it. We can see in this manner

that only the most worthy entrants were allowed to compete and those

dishonorable warriors were discouraged by harsh judgment and treatment.

The next day the crest and

banners are displayed and the ladies come to view them. René details how they

are walked around the hall to look at each participants=

gear. Heralds will tell the ladies who each participant is in case they do not

know them by their arms. This display of arms is really, in essence, a judgment

of the valor and merit of the participants and whether or not they will be

permitted to participate in the Tournament. René =s

treatise goes into great detail about how men who were guilty of several offenses

would be treated. It is as though they are seen as besmirching the glory and

honor of the Tournament by attempting to enter it. We can see in this manner

that only the most worthy entrants were allowed to compete and those

dishonorable warriors were discouraged by harsh judgment and treatment.

(This description of crests and

the illuminations in René’s book provides the SCA equestrian with excellent

source material for creating their own crests which can be used in SCA

equestrian activities.)

That night, at feast, the

judges announce that the two sides shall tomorrow present themselves to the

Tourney site. They also explain how each will follow ceremony and Apresent their oaths.@

And so, the following day, first the appellant, then the defendant,

comes to the field and with a great deal of pageantry announces their intent to

compete in the Tournament and abide by the rules. These list that Ayou will strike none of your company at

this tourney knowingly with the point of your sword, or below the belt, and

that no one will attack or draw on anyone unless it is permitted, and also that

if by chance someone's helm falls off, no one will touch him until he has put

it back on, and you agree that if you knowingly do otherwise you will lose your

arms and horses, and be banished from the tourney; also to observe the orders

of the judges in everything and everywhere.@

That day again ends with a

feast. At that feast a Knight of Honor is selected by the ladies. He will be tasked with indicating when mercy

should be shown to anyone who has committed some offense in the Tourney. A...if someone is too severely beaten,

the knight or squire will touch his crest with the veil, and all those beating

him must stop and not dare touch him because from that hour forward, the ladies

have taken him under their protection and safeguard.@

This veil, given to him by the Ladies, is called Athe

mercy of ladies.@ The

Knight of Honor will come to the Tournament with the judges before the

participants and after the ladies are seated, Afully

armed, with a helm with a crest on his head, and his horse covered with his

arms, ready to fight, the mace and the sword hanging from the saddle, carrying

the lance to which the veil is tied.@

So we have: the day of arrival,

the second day when crests are reviewed and merit measured, the third day when

oaths are made, and finally, on the fourth day, the Tournament.

The judges enter the arena and

check the lists. The Knight of Honor takes his place in between the barriers

and ropes, with his assistants. His helm is given to the Ladies to display near

them. Meanwhile, the appellant and

defendant sends word throughout the city for their men to gather together and

come to the Tourney field. The men are instructed that they should arm

themselves for the tourney, mount their destriers, and assemble at the inn of

their captains. The Heralds call them together, "Take up, take up your

helms, take up your helms, lords, knights and squires, take up, take up, take

up your helms and come out with banners to gather at the banner of your

captain." They meet up with their

captain and proceed to the Tourney field. They Ashould

have ... heralds... with them, and many trumpeters and minstrels sounding; and

the lord appellant's pennon should be carried before him by someone... After

this pennon should come the lord appellant, and at the tail of his horse

whoever carries his banner. And after him two knights banneret in front with

their banners, and twenty tourneyers, and then banners and tourneyers

alternately, and in such order they proceed to the barriers. And when they are

before the barriers, their servants should make a great cry; and then all the

knights and squires should lift their right arms over their heads, holding

their swords and maces, as if threatening to strike... and wait quietly.@

The Herald for the Appellant

announces him and his intention to enter the Tourney. The Herald for the Judges

replies, and welcomes the appellant, assigning a side in the Field to him and

his men. After a great cry from their

supporters, these warriors take up their place on the Field.

Afterwards the defendant and

his company, similarly assembled, enter the Tourney field. They are introduced,

welcomed and take up their place.

After both sides have readied

themselves, four men, specially selected for the task, cut the ropes dividing

the two lists from each other and the combatants do battle. AThen the two sides ....fight until by

the order of the judges the trumpets sound the retreat.@

Failure to stop fighting will result in a loss for that side.

René does not elaborate a great

deal on the fighting itself. He mentions how each participant can have a

man-at-arms to assist him should he fall from his horse. AAnd it is their job to take their

master out of the press when he asks and they can do it, always crying the cry

of their master.@ He

mentions how the tourneyers should retreat from the field after the retreat is

called, and how their pennons and banners should be removed from the field. AAnd they may go in troops fighting

among themselves to their inns, or without attacking each other, as they wish;

and in this way the tourney is finished and over.@

One must assume that some of these warriors, not content with the amount of

fighting to be had in the Tournament, continued fighting outside the Tourney

field. (This can be seen as similar to

SCA heavy fighters, following a battle, seeking pick-ups fights with one

another for the pure pleasure of testing themselves against each other.)

That evening a feast is held in

honor of the Tournament. At this feast, the Ladies award the prize of the

tourney to the fighter they deemed to have Afought

best today in the melee of the tourney.@ The Herald then announces that on the next

day there will be Jousting, by individuals and teams. While René does not mention the prize given

to the winner of the days Tournament, he does detail prizes for the Jousting to

be held the next day.

The first will be a wand of

gold for him who strikes the best blow with a lance that day.

The second will be a ruby worth

a thousand ecus or less, for him who breaks the most lances.And the third will be a diamond worth a thousand ecus or less, for him who stays the longest in the lists without losing his helm.@

The last section of René =s

work concerns the procedures for arranging for this next part of the

Tournament. He does not describe the Jousting phase itself, but discusses the

arrangements that need to be made to run this event. This includes finding a

good site, with a suitable hall for the feast, lodgings for the participants,

pay for those rendering services, etc. (very similar issues that concern any

Autocrat of the SCA.) And so, at the end

of his treatise, we see that the issues that Rene=

faced in his day, is not much different than those by current day Autocrats,

Marshals and event organizers.

René =s

Treatise provides us with a lot of source material to use as a guide in

planning a Tournament such as one held during the 14th and 15th centuries. It

was during that time that Tournaments reached their peak, and were the most

elaborate and celebrated of medieval martial displays. Though mounted melees

are not often the focus of SCA equestrian activities, we can still use René as

a basis for our own events, such as the Emprise. It also provides an

understanding of the historical significance of ABillets@ the arms displayed on wooden shields,

displayed at the Tourney field to identify the participants, as well as the

barriers, use of crests, and the heraldic discourse. All these things add to

the pageantry and the wonder involved in Living the Dream, the equestrian way!

King Renés Tournament Book, A Treatise on the Form and

Organization of a Tournament, translated by Elizabeth Bennett, can be found here.